Your lesson to me is the consequence of my own education. I have taught you to not love White people. That sentence may get me in trouble. Of course, you love individual White people. I do too. Many in fact. But I have taught you to not love them as a group. Because Whiteness as such means hating oneself. And I have taught you to love Black people. Of course, there are individual Black people that you dislike or even despise. I do too. There are Black people I dislike so much I don’t want to lay eyes on them. But loving Black people is not about each individual; it is about something bigger than that. Yusef Komunyakaa has a poem called “Blackberries.” In the middle it goes like this:

Although I could smell old lime-covered

rntHistory, at ten I’d still hold out my hands

rnt& berries fell into them. Eating from one

rnt& filling a half gallon with the other, I ate the mythology & dreamt

rntOf pies & cobbler

We hold open our hands for certain histories; we do make choices about what we will swallow, and dream.

Blackberries are one of those things I fed you, thinking that I was being a superior mother. I also made fresh baby food with a puree machine and avoided all unnecessary sugar. For a little while. Blackberries were unfamiliar to me until adulthood. When I started to eat them, I thought they were kind of fancy. I would place them in a bowl, a pale one, to contrast against their rich color. Early, I noticed that whenever the baby ate them, a thin angry rash grew. I took you to an allergist and she said you absolutely were not allergic to blackberries. But those rashes were uncomfortable. And persistent. And definitely directly correlated to the times when you ate a big bowl of blackberries. So, I kept them from you.

Sons—

rntYou have been running away from lies since you were born. But the truth is we do not simply run away from something; we run to something. I do not think you fully believe me, but I am not a mother who yearns for you to be a president or captain of industry. I will not brag about your famous friends or fancy cars, and I will not hang my head in shame if you possess neither. I am practical, to a certain extent. I want you to be able to eat, to keep a roof over your head, to have some leisure time, to not struggle to survive. I want you to be appreciated for your labors and gifts. But what I hope for you is nothing as small as prestige. I hope for a living passion, profound human intimacy and connection, beauty and excellence. The greatness that you achieve, the hope I have for it, for you, is a historic sort, not measured in prominence.

It is a kind rooted in the imagination. Imagination has always been our gift. That is what makes formulations like “Black people are naturally good at dancing” so offensive. Years of discipline that turn into improvisation, a mastery of grammar and an idea that turns into a movement that hadn’t been precisely like that before—that is imagination, not instinct. Imagination doesn’t erase nightmares, but it can repurpose them with an elaborate sense-making or troublemaking. This is what I take to be the point of the idea in Toni Morrison’s “Song of Solomon”: “Wanna fly, you got to give up the shit that weighs you down.” Flight is a way of transcending the material given in favor of the heretofore unseen.

Here is a confession: Recently, I have wondered if White people are irredeemable. Again, I have to issue a caveat for the sensitive. No, I do not mean individuals. Individuals are the precious bulwark against total desperation—in them we find the persistence of possibility. Of course a single person can be someone’s hell. But a single person can be a heaven too. Or a friend. But I worry that White people are irredeemable, and it scares me. What would the complete dissembling of the kingdom of identity look like? How would the viscera pulse under a cracked open surface? Would we all shatter? Could we put something together again? I don’t know. I am losing some of my ability to dream a world.

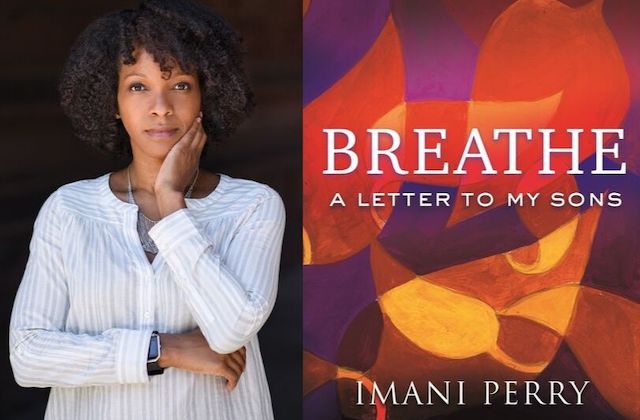

Excerpted from “Breathe: A Letter to My Sons.” Copyright 2019. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press. It’s available now.

Imani Perry is the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, where she also teaches in the Programs in Law and Public Affairs, and in Gender and Sexuality Studies. She is a native of Birmingham, Alabama, and spent much of her youth in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Chicago. She is the author of several books, including “Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry.” She lives outside Philadelphia with her two sons, Freeman Diallo Perry Rabb and Issa Garner Rabb.