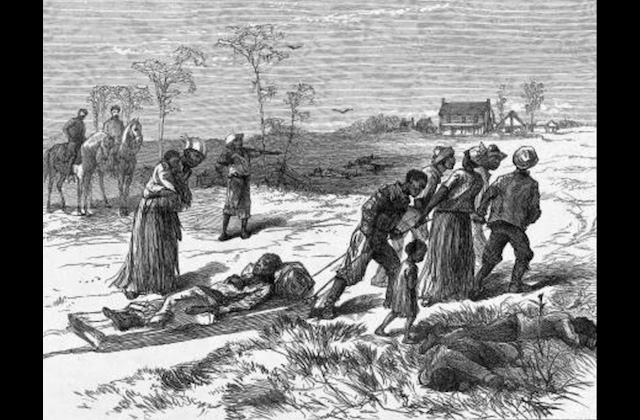

Today (April 13) marks 144 years since a White supremacist mob killed between 60 and 150 Black men in what became known as the Colfax Massacre.

Historian Eric Foner’s 1998 book, "Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877," describes the 1873 mass killing as "the bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era." It happened in Colfax, Louisiana, during the post-Civil War years where Republican coalitions—which included many recently-freed African Americans—fought Southern Democrats and White supremacist groups for government representation.

As outlined by Smithsonian Magazine, the massacre followed a tense Louisiana gubernatorial election, which Reconstruction-supporting Republican William Pitt Kellog narrowly won. Fearing that Democrats might react by taking over the local parish government, an all-Black militia occupied the local courthouse. On April 13, an armed group of Klansmen, White League members and former Confederate soldiers fired a cannon at the courthouse, prompting an armed skirmish that ended in the Black militia’s surrender. Upon that surrender, the mob proceeded to kill most of the surviving militia members by shooting and hanging.

Historical accounts of the death toll vary. Journalist Charles Lane’s 2008 book, "The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court and the Betrayal of Reconstruction," estimates between 61 and 82 Black men were killed. Meanwhile, a still-standing 1951 historical marker that calls the massacre a "riot" that "marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South" says 150 Black people and three White men died. Explaining the lack of clarity, historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. writes in The Root that "there was no opportunity for the Blacks of Colfax even to bury their dead in the trenches they had built until a deputy U.S. Marshall arrived two days later, Tuesday, April 15."

Gates writes that the massacre prompted federal charges against nine White mob members for violating the 1870 Enforcement Act, which allowed the government to prosecute anybody who violated freed Black Americans’ civil rights. The three men were found guilty, and appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1874’s United States v. Cruikshank, named for mob leader Bill Cruikshank. SCOTUS ultimately acquitted the men and ruled to leave civil rights prosecution up to the states. That decision paved the way for Southern Democrats to introduce Jim Crow and further consolidate power over Black citizens.