Between 2014 and 2015, 12 residents of Flint, Michigan, died from—and 87 others became ill with—Legionnaire’s disease. New research ties the outbreak directly to the water crisis that hit the city at that same time.

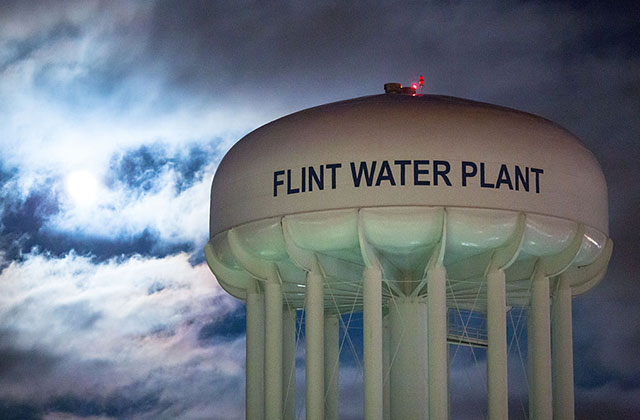

In April 2014, Flint switched its water source from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the Flint River. One year later, pediatrician Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha and scientists discovered there were high levels of lead in the water of the city, where 41.2 percent of the residents live below the poverty line and 56.6 percent of residents are Black. In addition, NPR reports, “Just months after the water source changed, hospitals were reporting large numbers of people with Legionnaires’ disease.”

Per NPR:

The bug can enter the lungs through tiny droplets, like ones dispersed by an outdoor fountain or sprinkler system, or accidentally inhaled if a person chokes while drinking.

"If you don’t have a robust immune system, the microbe can cause a lethal pneumonia," [Michele Swanson of the University of Michigan, who has been studying Legionnaires’ disease for 25 years] says. In a normal year, the disease is relatively rare—about six to 12 cases per year in the Flint area, according to Swanson. During the water crisis, that jumped up to about 45 cases per year.

The disease is caused by the water-born bacteria Legionella, whose levels rose as a direct result of the switch in the water source, according to new research that was released in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Monday (February 5) and the journal mBio today (February 6). The two studies were conducted by a team at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Sammy Zahran of Colorado State University and researchers from Wayne State University in Detroit.

The studies show that the new water source contained significantly lower levels of chlorine, which inhibits growth of the bacteria. In addition, “chlorine can react with heavy metals like lead and iron, and with organic matter from a river. That means lead and iron in the water may have decreased the amount of chlorine available to kill bacteria,” reports NPR.

Today, as Flint residents continue to deal with the consequences of the health and financial burdens brought by the crisis, the city’s water source has sufficiently high levels of chlorine to keep levels of Legionella bacteria low. Says Marc Edwards, one of the first scientists to report on the lead in water, "The system has never been less likely to support the growth of the deadly Legionnaires’ bacteria."