As the U.S. celebrates its 238th anniversary this week, during a year in which income inequality reached heights not seen in almost a century, now is as good a time as any to ask whether American democracy and its winner-take-all capitalistic system are compatible or need to part ways. It’s particularly important given the fact that people of color disproportionately suffer the negative consequences of the nation’s economic inequities even as they form an increasing demographic majority. How this question is answered is crucial to the immediate future of communities of color and by extension the country as a whole.

The facts of current income inequality are well known and are broadly not in dispute. The guru of income inequality, economist Emmanuel Saez, concludes that the top 1 percent of all income earners in the US have a greater share (PDF) of national wealth than at any point since 1928. For the uber-wealthy, the top .1 percent, the increased proportion of the economic pie is even more astounding. It’s on par with that of more than a century ago in 1913 during the nation’s so-called Gilded Age, when dramatic wealth was predicated on mass worker exploitation. Added to it all is the fact that inequality in the United States now exceeds that of every advanced economy on the planet except Chile’s.

Of course income inequality has dramatic economic consequences that are even more stark when viewed through the prism of race. According to the Federal Reserve more than nine out of 10 of the wealthiest American households are white. Since 2000, as Joseph Stiglitz has determined, nine out 10 dollars in economic gains in the U.S. have flowed to the richest. During this same time, black and Latino wealth has cratered to the lowest on record. Blacks and Latinos are more likely to have jobs where wages are at a 40-year low, be without work or live in poverty. Economic inequality in America has a black and brown face.

What’s interesting is that the growth in inequality occurred just as the doors of political power and economic opportunity were flung open to people of color. A set of professors from Columbia, Princeton and the University of Houston lay out the case in their 2003 paper "Political Polarization and Income Inequality (PDF)." What they show is that beginning in the 1970s, the political views of the wealthy began to harden against the very economic policies which had previously given everyone an economic shot. The authors, Nolan McCarty, Howard Rosenthal and Keith Poole, note that this turn against equality was so jarring because it "began after a long period of increasing equality" back in the 1930s.

But as important as the wealthy’s turn away from economic fairness and toward political movements created to prevent it is the way that this transformation was informed by race. "The bipartisan consensus among elites about economic issues that characterized the 1960s has given way to the ideological divisions" that are directly "linked to race," the paper says bluntly.

The key here is that there’s nothing about the transformation of our of political and economic system in the 1970s that was either inevitable or Act of God. Rather they are the result of specific choices, made at a specific time, with race at the heart of the change. As Stiglitz wrote recently, "widening and deepening inequality is not driven by immutable economic laws but by laws we have written themselves."

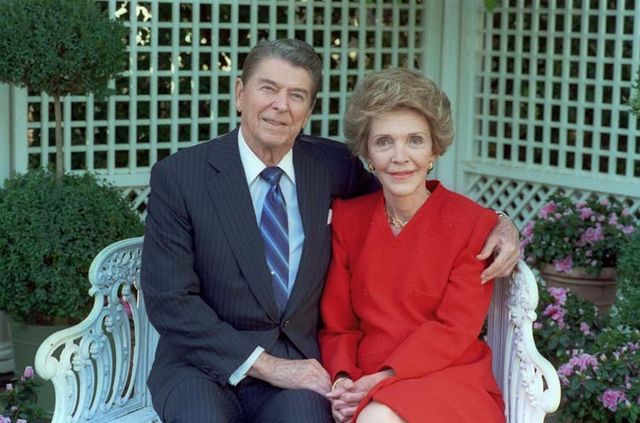

In the 1980s Ronald Reagan picked up on the changed mindset of the wealthy towards economic fairness, captured the White House, and implemented policies based on the ideals of the rich. Since then, besides a brief detour in Bill Clinton’s second term, inequality has been off to the races, erasing economics gains in one generation that took two generations to build. In fact the International Monetary Fund–the global organization focused on the health of the world’s financial structures–concludes that rich-oriented political policies benefitted the wealthy but ended up causing the financial and economic crisis of 2008.

Our experience with inequality over the past three decades brings us to the core of the precariousness of our current moment. Not only does inequity produce the type of recent inherent economic instability that we’ve already lived through but over time it’s politically unstable as well. Researchers Alberto Alesina and Roberto Perotti looked at 70 countries over a 25-year period and asked, "Does income inequality increase political instability?" Their answer conclusively was, "Yes…more unequal societies are more politically unstable."

With each passing year the strength of the political and economic system we’ve chosen to build since the 1970s will continue to be tested. As people of color move toward becoming the majority in America–should current trends hold–economic opportunity and the political influence necessary to bring economic change about could be out of reach for the black and brown democratic majority. We’re already seeing the beginnings for what what the future might have in store on this regard.

As the wealthy increasingly exercise their power to give unlimited contributions to campaigns and then use this power to fuel political efforts hostile to voting rights and economic justice, more and more Americans could find the instruments of democracy harder to exercise. What’s currently happening in North Carolina due to the efforts of the Koch Brother-backed Americans for Prosperity to fund a political backlash against economic fairness is a shining example.

The bottom line is that asking the question of whether a country in which economic gains are concentrated in fewer and fewer hands can also be a stable democracy is not an esoteric exercise. Actually, it goes to the core of who we are and what we stand for. And it has preoccupied America’s heart and soul since formal establishment in 1776.

Who gets to have an economic shot and who gets to have a vote through the recognition of their humanity form the center of gravity of a 200-year national debate that has yet to be fully resolved. But with the volatile mix of demographic change, economic inequality, political stagnation and the disproportionate empowerment of the wealthy, we may be in uncharted territory.

Yet what’s amazing about America is its capacity to change and renew itself, seemingly out of nowhere. The possibility for renaissance is perhaps more true now than in the beginning. More citizens have a say-so in what happens to a degree unimaginable nearly two and half centuries ago.

As Stiglitz put it, "It is only engaged citizens who can fight to restore a fairer America and they can only do so if they understand the depths and dimensions of the challenge."