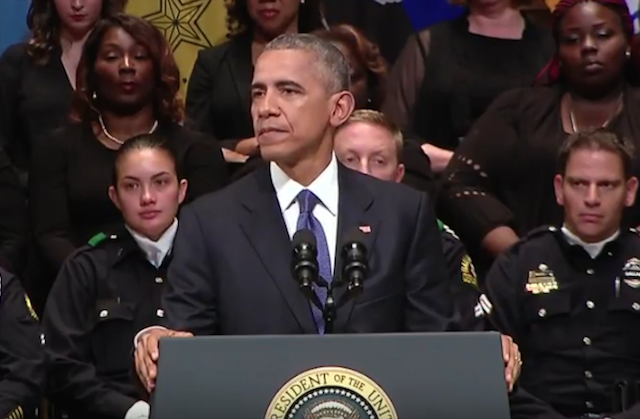

President Barack Obama delivered the closing remarks at a ceremony honoring the five Dallas police officers killed in the July 7 attack during a peaceful protest against police violence. He took the opportunity to make some very pointed remarks about the state of the relationship between police and people of color. Read them below and watch the full video here.

We also know that centuries of racial discrimination, of slavery, of subjugation, and Jim Crow, they didn’t’ simply vanish with the end of lawful segregation. They didn’t just stop when Dr. King made a speech and the Voting Rights Act or Civil Rights Act were signed. Race relations have improved dramatically in my lifetime—those who deny it are dishonoring the struggles that helped us achieve that progress. But, America, we know that bias remains. We know it. Whether you are Black or White or Hispanic or Asian or Native American or of Middle Eastern descent, we have all seen this bigotry in our own lives at some point. We’ve heard it at times in our own homes. If we’re honest, perhaps we’ve heard prejudice in our own heads and felt it in our own hearts. We know that. And while some suffer far more under racism’s burden, some feel to a far greater extent discrimination’s sting. Although most of us do our best to guard against it and teach our children better, none of us is entirely innocent. No institution is entirely immune, and that includes our police departments. We know this.

And so when African Americans from all walks of life, from different communities across the country voice a growing despair over what they perceive to be unequal treatment, when study after study shows that Whites and people of color experience the criminal justice system different—so if you’re Black you’re more likely to be pulled over or search or arrested, more likely to get longer sentences, more likely to get the death penalty for the same crime. When mothers and fathers raise their kids right and have the talk about how to respond if stopped by a police officer, “Yes sir, no sir,” but still fear that something terrible may happen when their child walks out the door. Still fear that kids being stupid, not quite doing things right might end in tragedy. when ll this takes place more than 50 years after the passage of the Ciivil Rights Act, we cannot simply turn away and dismiss those in peaceful protest as troublemakers or paranoid. You can’t simply dismiss it as a symptom of political correctness or reverse racism. To have your experience denied like that, dismissed by those in authority, dismissed perhaps even by your White friends, your coworkers, fellow church members again and again and again, it hurts. Surely we can see that. All of us.

We also know what Chief Brown has said is true, that so much of the tensions between police departments and minority communities that they serve is because we ask the police to do too much and we ask too little of ourselves. As a society, we choose to underinvest in decent schools, we allow poverty to fester, so that entire neighborhoods offer no prospect for gainful employment. we refuse to fund drug treatment and mental health programs. We flood commutes with so many guns that it is easier for a teenager to buy a block than it is to get his hands on a computer or even a book. And then we tell the police, “You’re a social worker, you’re the parent, you’re the teacher, you’re the drug counselor.” We tell them to keep those neighborhoods in check at all costs and do so without causing any political blowback or inconvenience. “Don’t make a mistake that might disturb our own peace of mind.” And then we feign surprise when periodically the tensions boil over. We know those things to be true. They’ve been true for a long time. We know it. Police, you know it. Protesters, you know it. You know how dangerous some of the communities where these police officers serve are, and you pretend as if there’s no context. These things we know to be true. And if we cannot even talk about these things. If we can not talk honestly and openly, not just in the comfort of our own circles, but with those who look different than us or bring a different perspective, then we will never break this dangerous cycle. In the end, it’s not about finding policies that work, it’s about forging consensus and fighting cynicism and finding the will to make change.

Can we do this? Can we find the character as Americans to open our hearts to each other? Can we see in each other a common humanity and a shared dignity and recognize how our life experiences have shaped us? And it doesn’t make anybody perfectly good or perfectly bad, it just makes us human. I don’t know. I confess that sometimes, I too, experience doubt. I’ve been to too many of these things. I’ve seen too many families go through this. But then I am reminded of what the Lord tells Ezekiel, “I will give you a new heart,” the Lord says, “And put a new spirit in you. I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh.” That’s what we must pray for. Each of us. A new heart. Not a heart of stone, but a heart open to the fears and hopes and challenges of our fellow citizens. That’s what we’ve seen in Dallas these past few days and that’s what we must sustain. Because with an open heart, we can learn to stand in each other’s shoes and look at the world through each other’s eyes. Because then maybe the police officer sees his own son in that teenager with a hoodie who’s kinda goofing off, but not dangerous, and maybe the teenager will see in the police officer the same words and value and authority of his parents.

With an open heart, we can abandon the overheated rhetoric and the oversimplification rhetoric that reduces who categories of our fellow Americans not just to opponents, but to enemies. With an open heart, those protesting for change will guard against reckless language going forward. Look at the model set by the five officers we mourn today. Acknowledge the progress brought about by the sincere effort of police departments like this one in Dallas. And embark on the hard but necessary work of negotiation, the pursuit of reconciliation. With an open heart police departments will acknowledge that just like the rest of us, they’re not perfect. That insisting we do better to root out racial bias is not an attack on cops, but an effort to live up to our highest ideas. And I understand that these protests—I see them, they can be messy. Sometimes, they can be hijacked by an irresponsible few. Police officers can get hurt. Protesters can get hurt. It can be frustrating, but even this who dislike the phrase Black Lives Matter, surely we should be able to hear the pain of Alton Sterling’s family. When we hear a friend describe him by saying that, “Whatever he cooked, he cooked for everybody,” that should sound familiar to us, that maybe he wasn’t so different than us. So that we can, yes, insist that his life matters. Just as we should hear when student and coworkers describe their affection for Philando Castile as gentle soul. “Mr. Rogers with dreadlocks,” they called him. And know that his life mattered to a whole love of people of all races, of all ages. And that we have to do what we can, without putting officers’ lives at risk, but do better to prevent another life like his from being lost. With an open heart, we can worry less about which side has been wronged and worry more about joining sides to do right. ’Cause the vicious killer of these police officers, they won’t be the last person who tries to make us turn on one another. The killer in Orlando wasn’t. Nor was the killer in Charleston.

We know there is evil in this world. That’s why we need police departments. But as Americans, we can decide that people like this killer will ultimately fail. They will not drive us apart. We can decide to come together and make our country reflect the good inside us, the hopes and simple dreams we share.