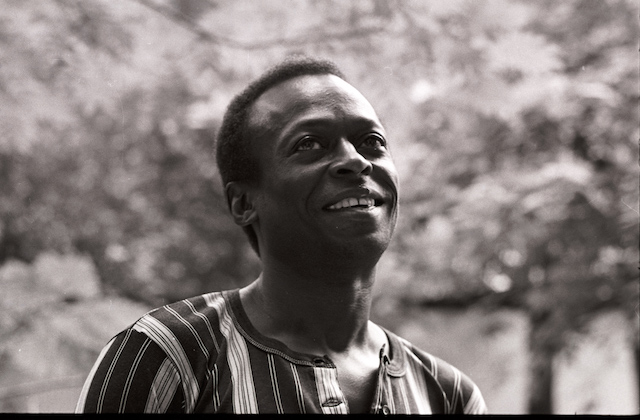

The title of Stanley Nelson‘s latest documentary, "Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool," references both the artist‘s 1957 jazz album and the inimitable swagger he carried throughout his career. From his musical innovation to his sartorial choices to his enigmatic public personality, Nelson says the trumpeter and composer embodied the definton of "cool."

"I challenge anybody to say who’s cooler than Miles," Nelson tells Colorlines. "That was an important aspect of who Miles was to us as an audience. Someone once said that [John] Coltrane came to the ‘Kind of Blue‘ sessions looking like he had slept in his suit. Coltrane didn’t care about clothes. Who knows what kind of car Coltrane drove? I don’t know! But I know what Miles drove. That’s who Miles was."

The film, whose premiere at Sundance Film Festival makes Nelson the annual gathering’s most prolific documentarian, connects this cool to Davis’ lifelong commitment to making genre-smashing art. Nelson intersperses chronicles of Davis’ most acclaimed albums, including "Kind of Blue" and “Bitches Brew," with interviews with writers and collaborators who describe his uncompromising vision.

While it focuses primarily on Davis’ creative contributions to jazz and the genres of music that grew out of it, “Birth of the Cool" does not feed the myth surrounding his life. It instead confronts it by exploring some of his worst moments: his substance abuse, assault by New York Police Department (NYPD) officers (one of several endured by prominent Black jazz artists) and physical and emotional abuse of his romantic partners. Members of Davis’ family, including ex-wife and dancer Francis Davis Taylor, describe his penchant for drug-fueled paranoia and violence in stark detail.

The film will air via PBS and in theaters later this year. On the heels of its Sundance premiere, Nelson spoke to Colorlines about the film, working with Davis’ estate and the art of narrative balance.

The Davis estate gave you access to much of the archival material in “Birth of the Cool." Given Davis’ famously mercurial personality and the inclusion of his story’s darkest chapters, did you face any hurdles with his family or other parties?

They’re very protective of Miles’ image. I kept in sporadic contact with the estate over the 15 years [that it took to get a final greenlight], so when we resurrected the project, we went out to California and met with Miles’ nephew Vince, son Erin and Darryl Porter, who’s the lawyer for the estate. We had a meeting, talked about getting this going, and it was kind of that easy.

Once they gave approval, we didn’t show them anything until they saw the final film a few weeks ago. We said that we’d use any music we wanted and figure out how to pay for it later on. There was no compromise for us, luckily. I should say this: there’s a little clip at the end when Miles plays with Prince, and the Prince estate was great. Part of it was Miles, because everybody loves Miles’ music.

{{image:2}}

"Birth of the Cool" also features several of Davis’ former partners speaking candidly about the ways that he hurt them. A lot of documentaries about influential male artists of Davis’ generation try to balance the art’s positive impact with the harm they caused women and children when the cameras were gone. Few manage to do so without positioning the abuse as part of what made them great. How did you avoid doing this?

I wish I had a great answer to that question, but it’s definitely something that we were concerned with throughout the entire process. We worked on that balance constantly. I think that one thing we do is go as far as possible in the interviews, so that you have the material, and you kind of figure out [the balance] in the editing room. We could’ve gone into a lot more detail about Miles’ abusiveness or drug use, but we didn’t want it to just be a horrid piece, but we had to make sure viewers understood that this was part of who he was.

Archie Shepp tells a story where Miles says, "Fuck you, you can’t play with me!" It helps in a lot of ways to show Miles as a normal person, as abusive and as rough as he could be to people. It was important to say that his story could be anybody’s. And it was important to show that this abuse was what he saw in his own parents, who had a mutually abusive relationship.

{{image:3}}

Speaking of the violence he witnessed, the section about the NYPD beating him bloody stands out. The film frames it as a moment that irreparably impacted Davis’ happiness, and as evidence that no amount of fame or creative achievement can protect Black people from racist violence. Did you set out to intentionally depict a sort of historical continuity in how our world treats Black art and people?

Obviously, there are connections, and we wanted to talk about this episode in the film. It’s a music film, a biography of this genius, but it’s also a film about racism in America. This is a unique position that you don’t see very often. He had everything, but Miles could say that he didn’t have anything, because he didn’t have the respect or freedom to operate safely in the United States. That’s one of the things that makes the story so interesting and rich, because of the effect it had on him.

{{image:4}}