In 2015, author Corinne Duyvis began the #ownvoices hashtag to highlight books where the author and main character share an identity. And while #ownvoices is especially important for Native people—who suffer from entrenched stereotypes of Hollywood Indians and a pan-Indian spirituality, both of which non-Natives love to peddle—some Native writers have moved beyond #ownvoices to #ownwords.

Indigenous words persevere despite efforts to extinguish our cultures, languages and selves. Nez Perce writer Beth Piatote and poet Heather Cahoon (Upper Kalispel) are creating portraits of Native communities deepened by each author’s use of her Native language. Both acknowledge her community as the primary audience, and each recognizes that levels of language proficiency vary greatly. But each word remembered and used strengthens the ties between present, past and future.

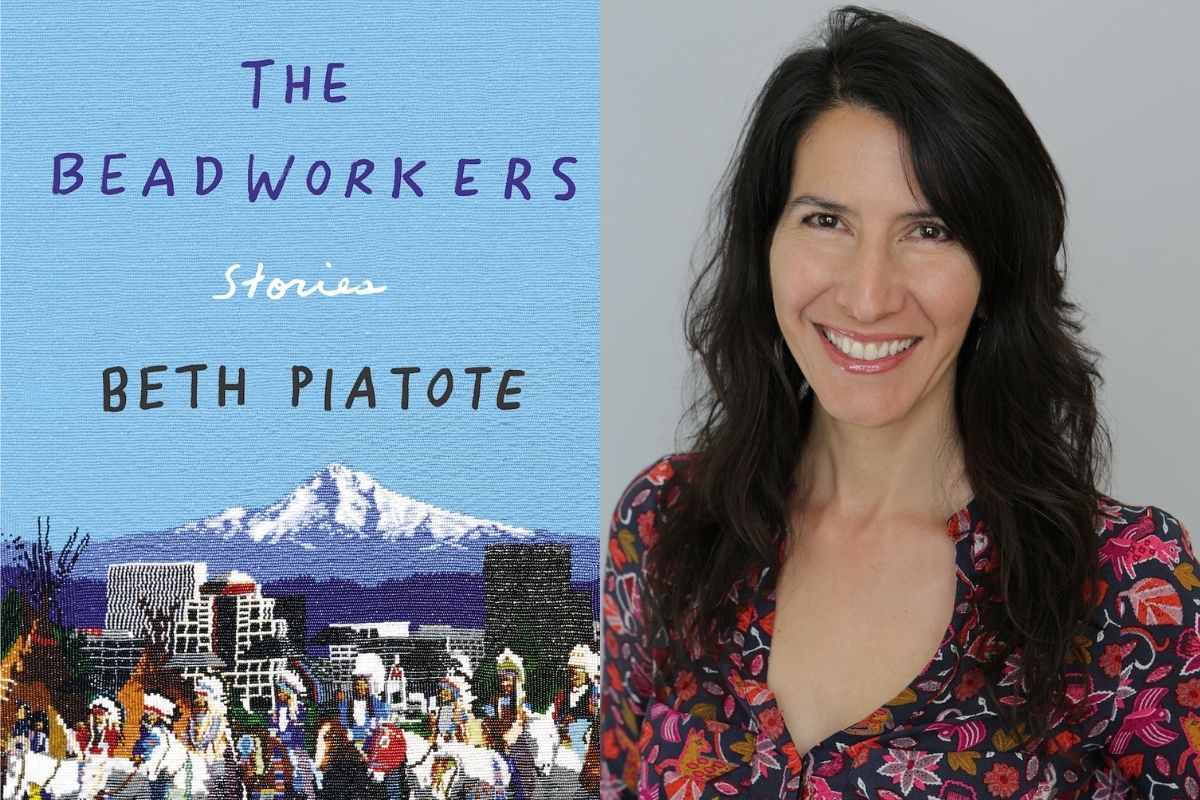

Piatote, an associate professor of Native American studies at the University of California at Berkeley and studies the Ni:mi:pu: [Nez Perce] language and literature, released "The Beadworkers" (Counterpoint Press) in 2019. The paperback edition came out on October 22.

Her exquisite collection renders stories in various forms: poems, a story interspersed with instructions for a board game: “wIndin: THE EXHILARATING GAME OF KINSHIP, CHANCE & ECONOMIC REDISTRIBUTION, AGES 5 AND UP, HIGH PLATEAU EDITION,” and a play, “Antíkoni,” a revision of Antigone via a Nez Perce-Cayuse family, as well as more traditional short stories.

The collection is warm and inviting, despite the struggles characters face when, for example, they hold their families together during the Fish Wars for traditional treaty fishing rights in the mid-1960s, or as they support family returning with injuries from combat.

The collection opens with a triptych describing a traditional feast. It’s as if Piatote has invited the reader to a meal, and it’s so typical of Native people to feed each other. Like others, it’s important to remember family and honor our ancestors with tribal ways as we’ve been charged to do.

She uses the Nimipuutímt language to announce each food as it is traditionally presented in a prescribed order, embedding her culture in the text. Reading this poem echoes the feeling of going to an Osage traditional meal, where we honor our Osage ways. I’m buoyed by the reverence in the text.

Piatote doesn’t translate words, since they’re not translated at the feast in real life. But she does give context in the poem, moving from water to salmon, “turning in salt waters” to “travel through ocean waves.” The salmon labor to return to the cold rivers of their origin far upriver “where wewúkiye bugle/in fog-mantled mornings of our land.” In “Feast II,” nonfiction fragments offer context for non-Nimipuutímt speakers.

Using Nez Perce without translation is a nod to the future, an affirmation that there will always be Nez Perce speakers, Piatote said in a 2019 interview with the podcast Think Out Loud.

Piatote didn’t speak Nez Perce as a child, so she began to study with her aunt Theresa Eagle, a native speaker who lived on the Umatilla Reservation in Pendleton, Oregon. Several stories in the collection deal with language preservation, with the beauty and grace of acquiring language. She writes about speaking Nez Perce in a dream, being buoyed by that hope. She writes, “Later I would learn another word, and I would hold it just as close.”

Piatote’s stories also reflect the intersectionality of Indian Country. In “Katydid,” a character says:

These days, I suppose a sociologist would call me an urban Indian, but in Salem we were suburban Indians at best. And if I had to be honest . . . Basically I’m a farm Indian, a demographic absurdity: half Nez Perce, quarter 4-H, quarter Coors Longneck.

Native writers have a reputation for sliding across genres, writing both poetry and prose. While Piatote is breaking forms, Heather Cahoon is both an award-winning poet and a talented visual artist, holding poetry readings surrounded by her paintings.

rn{{image:2}}

"Horsefly Dress," Heather Cahoon’s first full-length collection of poetry, was released from the University of Arizona in September, following an award-winning 2005 chapbook, Elk Thirst. Cahoon is an assistant professor of Native studies and director of the newly launched American Indian Governance and Policy Institute at the University of Montana.

Cahoon’s poetry is a tender, careful accounting of the physical, emotional and spiritual manifestations of the Flathead reservation in Montana, where she grew up. The title poem tells of “an outpouring of primordial story,” namely Cahoon’s engagement with Coyote’s sister. Coyote is an important figure in her tribe’s oral history, Cahoon notes, but his sister is little referenced. In “Horsefly Dress” and throughout the volume, Cahoon is traversing “the divide between known and unknown,” between what is and is not spoken.

If her poems are grounded in place, as in the titular poem, “along Flathead River/ near Revais,” they also record the history of loss.

In “Wasp,” Cahoon delivers both a stinging indictment (“see colonies/busy building their homes on your land. With self-privileged aggression”) and a wry comment on WASPs. Regarding the settlers we Osages watched encroaching in Kansas—and Natives watched from coast to coast—the poet advises: “Open your mouths and let out your breath … Believe/ that the paper-winged buzz will weaken/and become ever fainter until/the only sound left is that of your singing.”

Cahoon uses Salish words to reclaim some of the space Salish and Kalispel people and their ideologies have held in the past. She’s said:

The words call attention to the fact that, like other tribal and Indigenous languages, Salish has been continuously spoken for thousands and thousands of years and both the language and people are still here despite very aggressive language prohibitions and acculturation efforts perpetrated by the federal government.

Readers, too, can feel the depth of the words spoken continuously for thousands and thousands of years in this place. Hear Cahoon read Łčíčšeʔ.

The use of one’s language on the page affirms a Native audience, a reverence for one’s language, and for persisting in the face of historic attempts to extinguish our ancestral languages and cultures.

For Native readers, seeing a writer’s ancestral language in use sparks celebration, especially since for so many of us, words for our family relations, nouns or prayers are all that remain for us. Our Native words and phrases encapsulate our people’s ways of seeing. They embody a worldview and kinship relations. Their use affirms our continuity and survivance.

No, “survivance” isn’t a typo—it’s a very particular word that signals Natives’ refusal to merely survive genocidal colonization. It affirms our vitality and the vibrant future that both Piatote and Cahoon draw.

Ruby Hansen Murray is a columnist for the Osage News. A citizen of the Osage Nation, she lives along the Columbia River. Visit her website at www.rubyhansenmurray.com